DDB

DO THIS OR DIE

The DDB (Doyle Dane Bernbach Inc, now called DDB Worldwide Communications Group Inc) is an advertising agency which was funded in 1949 by it's founder, Bill Bernbach, Ned Doyle and Maxwell Dane. Bill Bernach was considered one of the most important people in the formation of the “Creative Revolution” of the 60’s decade.

He described the ideology of the company with the phrase; "All of us who professionally use the mass media are the shapers of society. We can vulgarise that society. We can brutalise it. Or we can help lift it onto a higher level."

Since the early years of when the company formed, it had been distinguished for its philosophy which had an approach into respect for consumers, human nature, and the belief that "creativity is the most powerful force in business."

Swiss style had a huge influence on the designers of the sixties due to the internationalization of movement in the industry during that time. From this style, the work of this period took its simplicity and principle to communicate the message as clearly and objective as possible without distracting the audience by using ornaments, or 'decorative design' like in illustrations of past times.

DDB's philosophy explains how it was possible that such a company with so well known reputation at the time had submitted an entry to an ad contest, and won which was entitled "DO this or DIE". This was not even an advertisement but a critique to the companies. It raised the subject of focus in offering good products to the market which are valuable to make publicity of, instead of tricking the public by advertising products that are bad to begin with.

The extremely large heading in bold sans serif type, taking up nearly half the page, catches the viewer's attention to begin with, especially with the red lines above and below it. The phrase is them even more striking and stated as a fact, using the full stop at the end. This is simple, clear and shocking. The text below, then reads;

Is this ad some kind of trick?

No. But it could have been. And at exactly that point rests a do or die decision for American business. We in advertising, together with our clients, have all the power and skill to trick people. Or so we think. But we're wrong. We can't fool any of the people any of the time. There is indeed a twelve-year-old mentality in this country; every six-year-old has one. We are a nation of smart people. And most smart people ignore most advertising because most advertising ignores smart people. Instead we talk to each other. We debate endlessly about the medium and the message. Nonsense. In advertising, the message itself is the message. A blank page and a blank television screen are one and the same. And above all, the messages we put on those pages and on those television screens must be the truth. For if we play tricks with the truth, we die.

Now. The other side of the coin. Telling the truth about a product demands a product that's worth telling the truth about. Sadly, so many products aren't. So many products don't do anything better. Or anything different. So many don't work quite right. Or don't last. Or simply don't matter. If we also play this trick, we also die. Because advertising only helps a bad product fail faster. No donkey chases the carrot forever. He catches on. And quits. That's the lesson to remember. Unless we do, we die. Unless we change, the tidal wave of consumer indifference will wallop into the mountain of advertising and manufacturing drivel. That day we die. We'll die in our marketplace. On our shelves. In our gleaming packages of empty promises. Not with a bang. Not with a whimper. But by our own skilled hands.

DOYLE DANE BERNBACH INC.

Not many advertising companies, of that time, or even now, would have published a text which criticises the same field they work for, but DDB were not afraid to. It is honest, insightful and above all, treats it's audience like it is intelligent enough to not be, or to at least stop being, consumer monkeys.

By the same principle, the Volkswagen Beetle adverts are a prime example of intelligent marketing.

In 1959 DDB created the famous 'Think Small' Volkswagen campaign, and told people to think on an VW as reliable, simple, different and an honest car.

This ad goes against the 'big american dream' of having everything and making it larger than life. Adds of that time were glamorous, attractive, and above all, did not appeal to those who did not have vast amounts of money to afford such luxuries, which was the majority. The 'think small' ad encourages them to feel okay about wanting something reliable, useful and affordable. It communicates to them on their level, rather than talking down to them with images of beautiful scantily-clad women leaning on an oversized, fuel guzzling 'dream car'.

Instead, it features merely a mass of white space and a tiny Volkswagen Beetle off centre of the page. The centred text is not large and over-powering, but simple, as if just a suggestion. This makes the viewer think that getting the car was their idea, not the advertiser's, who would usually tell them that they need it, not that it might be useful. The Volkswagen logo is also very small, as to not draw too much attention to the company, but again, just suggests the brand.

This ad, again using the same layout and small type, also puts across a strong message. In America, the term lemon is an insult to mean useless. The advertisers insult their own product by calling it by this name due to its size, which encouraged the consumers to think differently about what they are buying; to think about practicality and what is best for them, not the guys who make the money out of it. It looks like any other car ad, apart from the title, which makes it stand out from those in a subtle and intelligently humble way.

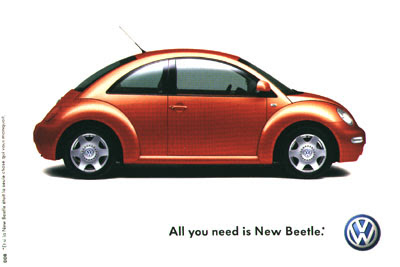

The campaign was so effective that it increased sales and also influenced the design of the 1998 campaign for the launch of the new Volkswagen Beetle. It used the same ad with only minor changes, to demonstrate its superiority over other campaigns.

The ad was simply a car, a logo and a strap line. Now colour ads can be published, the use of bold colour can help attract consumers, which the bright orange does, but that is the only punchy thing to do so. The logo is slightly larger and more memorable in blue, than on the old ads, but still not plastered all over, as if trying to brainwash people into needing the product. Also, wether the pun was intended or not, a flash back to it's hay day is hinted at with reference to the band from the 1960's, 'The Beatles', by using the name of the car and 'all you need', from one of their most famous songs which have the lyrics 'all you need is love'.

No comments:

Post a Comment